The history of osteoarthritis - Episode 1

Osteoarthritis, the price of being bipedal?

Bipedal walking is not unique to humans (some monkeys are able to walk on two limbs as were hominids as well).

It is actually this exclusive bipedalism which, among other things, contributes to the uniqueness of Homo sapiens sapiens and their direct predecessors or closest relatives (such as Neanderthal Man).

This evolution was accompanied by skeletal adaptations favouring the dynamics of walking, the highest form of which is found in modern humans.

Walking continuously with both lower limbs leads to advantages such as freeing the hands. Another consequence of our less fortunate "upright" position: the considerable increase in weight and pressure on certain joints, such as the hip and spine.

The evolution of our skeleton only enables us to withstand the weight in an incomplete way and the joints of the lower limbs have to continuously bear the weight of the upper body when walking or even when standing still. Carrying loads only adds to the pressure on the hips, knees and spine.

Bipedalism might then in itself be a "mechanical" risk factor of osteoarthritis. What goes against this hypothesis is the fact that some quadrupeds are equally affected which suggests that the mechanisms of this disease are somewhat more complex.

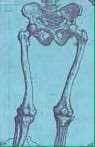

Exclusive bipedalism requires good force distribution.

When standing, the force exerted on each hip is equal to half the body weight reduced by the weight of both lower limbs

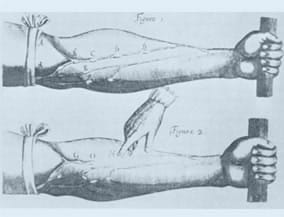

In modern humans, the anatomical features of the joint can "relieve" the joint by distributing the force as shown in the sketch above.

This distribution tends to produce a zero kinetic "moment".

- PC = force produced by the weight of the body

- A = force produced by the abductor muscles

- R = reaction force of the joint.

Lucy walked with a very swaying posture when she was not climbing trees.

The most famous of hominids is probably Lucy, the female Australopithecus afarensis discovered in 1973 by Y. Coppens, M. Taieb and B. Johanson in Ethiopia where she lay peacefully for about 3 million years.

According to current thinking, Australopithecines are not our direct ancestors, but more or less distant cousins.

Lucy's pelvis, wider than ours, and the pronounced direction of her femurs towards the median line (such as a modern woman with a femur deformity indicating coxa vara and genu valgum types of deformity) suggests that she had to walk with a heavily swaying posture in fairly brief episodes of bipedalism (a few tens of metres according to the footprints discovered in Laetoli, still in East Africa). Her upper limbs, longer than in humans, and the less restricted movements of her shoulder show that Lucy must, in fact, have spent a lot of time in the trees.

Genu Valgum

Lucy could therefore settle for a femur head much smaller than ours to perform limited journeys during which she briefly increased weight and pressure on her hips, without increasing her risk of osteoarthritis of the hip of mechanical origin.

Evolution of the axis of the lower limb (in relation to bipedalism)

… 3.6 million years ago two Australopithecus afarensis (one much smaller than the other) walked side by side in a plain of northern Tanzania, leaving their footprints on volcanic ash which the rain transformed into a sort of plaster.

In drying, this material was to take on the properties of a concrete hard enough to preserve these footprints to the present day. These footprints tell us that a step began when the heel struck the ground and ended with a push of the toes. We do not do otherwise.

…and Neanderthals had a bent forward look

Let's casually skip a few million years to take a look at Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, a European who witnessed the arrival of Homo sapiens sapiens and, like him, was descended perhaps from Homo erectus.

Neanderthal had a curved femur with a concavity towards the front. Also adept at shifting from one foot to the other, Neanderthals had to walk very much bent forward. His bipedalism is thus accompanied by a weight distribution very different from ours, without being able to say whether, because of this, he was more or less susceptible than us to osteoarthritis.

In addition, the many fractures observed on Neanderthal skeletons suggest a perilous life, probably too short to reach the age at which this disease begins to manifest itself!

The history of osteoarthritis - Episode 2

Osteoarthritis in ancient times

The invention and use of writing, the birth of the first great civilizations: we have moved from prehistory to Antiquity.

The first medical treatises were soon to appear. The archaic conceptions involving gods and demons in the sickness and healing process were gradually replaced by a more rational approach based on observation but also on empiricism.

To find out what the concepts of the ancients for osteoarthritis and its treatment were, let's review the works of classical authors, examine the Egyptian mummies and finish this stage of our journey in China.

- The strange silence of Greek physicians

- Egypt at the time of the Pharaohs: osteoarthritis of the hip for the scribes, vertebral osteoarthritis for the peasants!

- And our ancestors the Gauls?

- Rome, osteoarthritis and herbal medicine: Dioscorides attributed therapeutic virtues to ivy.

- And acupuncture, since the earliest times.

The strange silence of Greek physicians

While texts on diseases of the bones and joints written by the founding fathers of Western medicine (Hippocrates, Celsus, Galen) thoroughly describe how to reduce the number of fractures and dislocations and how to treat war wounds (stabbings), no chapter is devoted specifically to rheumatic diseases.

Hippocrates (470 - 410 av. J.-C.)

Taking the example of Hippocrates and his 412 famous Aphorisms, only six of them, of which here is a rough translation, refer to rheumatism:

- In the elderly, dyspnoea, catarrh and coughing, dysuria, joint pain, kidney inflammation, vertigo, etc.

- Swelling and joint pain, ulcers, those of a gouty nature and muscle strain are usually improved by cold water, which reduces swelling and eliminates the pain, as a moderate degree of numbness eliminates pain.

- In gouty disorders, inflammation disappears within 40 days.

- Typically, gouty disorders are exacerbated in the spring and autumn.

- In chronic diseases of the hip joint, where the bone comes out of its socket and then returns, indicates mucosities in this region.

- In people with a chronic disease of the hip joint, if the bone comes out of its socket,

the limb atrophies and is lost unless the site is cauterised.

The only rheumatic disease clearly identified in these lines is gout. It is difficult, however, to recognise hip osteoarthritis in the last two of these aphorisms which are otherwise very unsavoury: Hippocrates seems rather to refer to an evolved form of infectious arthritis. Osteoarthritis appears only implicitly among the joint pain affecting older people, but we know that such pain can be of various origins.

Why the apparent lack of interest in osteoarthritis as such?

Could the short life expectancy of the Ancients account for a logical disinterest in age-related diseases? Would mechanical factors leading to osteoarthritis have made this disease a disease of slaves, doing the toughest jobs, but regarded as mere instruments unworthy of interest?

In reality, we are with Hippocrates at the very beginning of the rational approach to medicine. Everything remains to be invented, beginning with the identification and accurate description of the disease (or nosography).

However, osteoarthritis has existed since ancient times. Demonstrated by the techniques of spinal manipulation (very unwise!) recommended by Hippocrates and more accurate data that has survived from ancient Egypt. Egypt at the time of the Pharaohs: osteoarthritis of the hip for the scribes, vertebral osteoarthritis for the peasants!

Some perfectly preserved skeletons dating from the Pharaonic era indeed provide valuable information on the existence of several rheumatic diseases! We thus know that ankylosing spondylitis, an inflammatory disease mainly affecting the joints of the lumbar region, has existed at least since the third millennium BC.

Pharaonic Egypt>

Osteoarthritis is not lagging far behind and osteoarthritic joint damage, common in Pharaonic Egypt, even gives some indication of the occupational activities of the sufferers.

The "office" work of that time did not confer any protection against osteoarthritis. Scribes and viziers sat cross-legged which predisposed them to osteoarthritis of the hip. Moreover, we find the predisposing factor at the present time in regions of the world where sitting cross-legged is one of the favourite resting positions. Egyptian peasants, constantly bending down and straightening up were more likely predestined to develop early bone spurs (osteophytes) characteristic of osteoarthritis of the spine. At the present time, these osteophytes appear in most people only from around the age of 50 years onwards and affect virtually all people of 90 years and over.

Egyptian documents reveal that the joint pain was treated with ointments containing fat, oil, honey or bone marrow, to which could be added the most diverse ingredients: flour, baking soda, onion, cumin, incense and so on. According to some sources the Egyptian peasants still use it today in the form of ointments with animal fat from snakes and lizards in an attempt to relieve rheumatic pain.

And our ancestors the Gauls?

The little known story of the Celts or Gauls (the two terms being synonymous before Julius Caesar reserved the second term for the Celts of what are now France and Belgium) extends over more than a millennium over the whole of Europe. In the sixth and fifth centuries BC, the first Celtic "Princes" appeared in Central Europe. A princely tomb was discovered intact in Hochdorf, near Stuttgart (Germany).

The Prince of Hochdorf delivered valuable information to archaeologists because he was surrounded by everything you need to travel conveniently in the other world (weapons, jewellery, dishes). A man measuring 1.87 metres. However, he suffered from osteoarthritis of the joints and his teeth were half worn down. He was also suffering from periodontal disease.

Rome, osteoarthritis and herbal medicine: Dioscorides attributed therapeutic virtues to ivy.

Dioscorides was a Greek physician, but he worked in Rome in the 1st century AD at the time of Nero. Author of the book De Materia Medica, translated and plagiarised many times over, and ancestor of phytotherapy or herbal medicine (his descriptions of plants, however, contain many errors), he recommends using ivy against what seems to be osteoarthritis of the hips. A remedy from which we could probably expect a good placebo 1 effect, as with the Egyptian potions.

1: Patients who volunteer to participate in studies measuring the effectiveness of current drugs are often randomly divided into two groups. In one of these groups, patients receive the active drug being studied. In the other group, patients receive a completely inactive "placebo" but whose appearance is strictly identical to that of the active drug.

During the study, neither the physician nor the patient knows which of the two products was used. It is known that up to 30% of people "treated" with a placebo administered with sufficient conviction by the doctor can feel an improvement in subjective symptoms such as pain. This suggests that Dioscorides obtained some "improvements" in his patients, even if he ignored that to be considered truly active, a drug must be significantly more effective than the corresponding placebo.

And acupuncture, since the earliest times.

Let's leave the countries bordering the Mediterranean and push on to the East. The oldest book devoted to Chinese medicine is "Neiching", also known as the "The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine." The book is written in the form of a dialogue between the Emperor "Huang Ti" and the doctor "Chi Po." The Yellow Emperor, supposed to have lived around 2700; BC, is in fact a legendary figure.

In fact, the "Neiching" seems to be a compilation written by several authors between 2500 and 1000; BC. This is, in particular, the first reference book on acupuncture. The techniques described have remained virtually unchanged until today, where acupuncture is sometimes used in the symptomatic treatment of pain caused by osteoarthritis.

The history of osteoarthritis - Episode 3

Osteoarthritis in the middle ages

Osteoarthritis in the Middle Ages was not yet at the centre of medicine which was gradually reuniting its knowledge, creating its schools and beginning to differentiate itself from the other sciences.

We will see in our next special feature, osteoarthritis in the Renaissance, how, with the progress of surgery, the development of schools and attitudes changed the way of thinking, what the common rheumatic diseases were and how they could be treated.

Some incipient forms of a still little known illness.

It has often been stressed that herbal medicine and mediaeval medical treatises contain more cures for eye diseases than all other diseases combined. That will surprise those who think that rheumatic diseases, particularly osteoarthritis, should be common in the Middle Ages when arduous labour was not lacking.

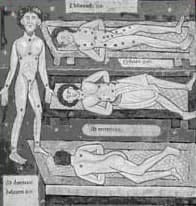

In reality, this "neglect" of doctors of the Middle Ages could have the same explanation as that of "the strange silence of Greek physicians." Anthropologists tell us that the incipient form of osteoarthritis existed in the Middle Ages, but the extremely short life span of our ancestors did not allow the disease to evolve towards severe forms.

Ancestors who were at risk of having remedies applied that were worse than the disease and being prescribed bloodletting at every opportunity. Indeed, despite some progress achieved, in particular, by Arab physicians, medical knowledge progressed very little in the Middle Ages. On both sides of the Mediterranean, we ardently copied the works of Hippocrates and Galen. More precisely, the Arabic translators were the first heirs of ancient knowledge; it is often Latin translations of Arabic texts that enable Western scholars to discover classical authors!

Yet, let us not forget, that in the Middle Ages the first Faculties of Medicine appeared, including the very first one, the School of Medicine of Montpellier, where the first dissections were performed. This work prefigured the growth of anatomy which took place during the Renaissance.

- Lessons of anthropology

- Theory of the humours and mediaeval treatments

- Medicine and the Arab schools

- The first Faculty of Medicine in the world was created in Montpellier

Lessons from anthropology

Osteoarthritis existed in the Middle Ages, but severe cases must have been rare

This is, for example, what the study suggests of the skeletons of 252 individuals who lived in the area of Brandenburg (Germany) between the 13th and 16th centuries. All belonged to the town of Bernau. Their main activities, agriculture and crafts, provided them with relatively good living conditions for the time. However, 52% of the individuals studied had died before the age of 20 years and life expectancy was only 25 years. It is therefore hardly surprising that, while most of the skeletons of the 85 adults of this population had evidence of osteoarthritis, it was only incipient forms of mild to moderate severity.

A team of Swiss researchers gives us more specific information. The study of 273 adult skeletons that lived in the Neolithic and the Middle Ages shows the absence of osteoarthritis of large joints such as the hip. Two other rheumatic diseases, rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, are also absent. However, these distant ancestors could have been suffering from osteoarthritis of the spine (cervical, dorsal and lumbar). Curiously, this condition appears to have been more common in the Middle Ages than the Neolithic Age. An effect of longer life?

By studying a much larger series of skeletons (695 Saxon or those of the English Middle Ages), British researchers effectively found signs of osteoarthritis (hip OA) in 29 of them. Knee osteoarthritis is also present but mainly affects the patella (14 cases) and very little the knee joint (4 cases). The authors conclude that the latter type of osteoarthritis may be of recent onset.

References

- Kramar C, Lagier R, Baud CA Rheumatic diseases in Neolithic and Medieval populations of western Switzerland. Z Rheumatol. 1990 Nov-Dec;49(6):338-45.

- Faber A, Hornig H, Jungklaus B, Niemitz C. Age structure and selected pathological aspects of a series of skeletons of late medieval Bernau (Brandenburg, Germany). Anthropol Anz. 2003 ; 61 :1 89-202.

- Rogers J, Dieppe P.Is tibiofemoral osteoarthritis in the knee joint a new disease? Ann Rheum Dis. 1994 Sep;53(9):612-3.

Theory of the humours and mediaeval treatments

In the Middle Ages in the West, sickness was often a result of Heavenly intervention and prayer was essential for healing. The doctors, however, were inspired by theories of the ancient Greeks (approved by the Church) that four "humours" in humans reflect the four basic elements of the World:

- yellow bile (corresponding to fire) makes a person violent and choleric;

- phlegm (corresponding to water) is responsible for pallor, fatigue, lack of courage;

- atrabile or black bile (corresponding to the earth) gives gluttony, laziness, melancholy;

- blood (corresponding to the air) makes the person joyous, generous and loving.

These four humours must be balanced for an individual to remain healthy. The diagnostic task of the physician was thus to determine, by observing the patient, what humour had taken over. Fever indicated that it was yellow bile, while coolness and perspiration pointed to phlegm. In any event, bleeding, by opening a vein or applying leeches, was a method widely used to balance the humours. Some preferred administering hellebore: the humour in excess was then removed by the violent diarrhoea and vomiting provoked by this treatment.

A precursor of aspirin was among the medications of the Middle Ages.

"Drugs" were also prescribed, including some, such as precious stones, which were used for their magical properties. More seriously, willow bark concoctions were recommended, from the time of Hippocrates to treat fever and certain types of pain, perhaps including rheumatic and notably osteoarthritic. This empirical treatment has found its way into the era of scientific medicine, since it is from willow bark that modern chemists extracted the first molecules of aspirin.

Medicine and the Arab schools

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the ancient knowledge was first collected by the Byzantines. From the 9th century, the works of ancient Greece or the Byzantine Empire, including medical treatises, were translated and studied throughout the Muslim world. Thus, what can be called the Arab schools came into being, with a strong influence and in which a few people stood out primarily by their philosophical and theological works, but also by their medical or surgical works.

Among the most famous :

- Rhazes (Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakaria ar Rasi), who worked in Baghdad in the ninth century. He described smallpox and measles.

- AbulCassis or Albucasis or (936 - 1013) whose reputation as a surgeon extended well beyond Cordoba. He wrote a famous treatise where he argues that medicine and surgery make up the same discipline.

- Avicenna (Abu Ali Ibn Abdullah Ibn Sina, 980-1037), author of the "Canon of medicine" to be widely distributed in the West after being translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona.

- The Jewish doctor Maimonides (Moses ben Maimon, 1135-1204), born in Spain and in exile in Cairo, where he became a famous philosopher and physician attached to the court of the Sultan.

- Avenzoar (Abu Marwan Abd al-Malik ibn Zuhr 1091-1162), from Seville, who was particularly interested in brain diseases, but best known for being the master of Averroes.

- Averroes (Ibn Rushd, 1126-1198), a great admirer of Aristotle and nicknamed in Europe for this reason as "the Translator" or "the Commentator." Author of a famous medical treatise known as the "Colliget," which would be translated several times into Latin and Hebrew. After holding the highest offices, Averroes fell from grace for defending the philosophers against the theologians.

Abulcassis had great influence in the West where some of his students and patients came from. This innovative surgeon already carried out his sutures with catgut (resorbable catgut is still used today in surgery). He performed surgery, in particular, bone surgery, and was probably the first to ablate the patella. In patients with patellofemoral osteoarthritis?

The first Faculty of Medicine in the world was created in Montpellier

The world's first Faculty of Medicine

Hospitals, usually created by monks, soon appeared in the Christian West (Paris, St-Julien-le-Pauvre was founded in 577 and the Hotel Dieu in 650). But it was in 1220, in Montpellier, then under the suzerainty of the King of Aragon, that the world's first Faculty of Medicine was created.

The geographical location of Montpellier, the historical context of the 12th and 13th centuries and the policy pursued by Guilhem VIII, Lord of Montpellier, appear to be the source of this remarkable event.

A city at the crossroads between Italy and Spain, close to the Mediterranean and the road to Saint Jacques de Compostela, Montpellier hosted many pilgrims, some of whom were sometimes tired and sick hence hospitals had to be created for them. Saracens and Jews participated in the development of knowledge and were not uncommon in this well-located market town.

In 1181, Guilhem VIII granted permission for "physics" (medicine) to be taught in Montpellier, to all those who wished to attend, irrespective of where they were from. Arab and Jewish doctors, expelled from Spain by the Catholic Monarchs after the Reconquista, facilitated the birth, 40 years later, of the first School of Medicine. They brought with them the traditions of Greek physicians, but also of Razès, Averroes, Avicenna, Maimonides and AbulCassis.

Up until the 14th century, the courses of the School of Medicine of Montpellier were given at the teachers' homes.

Two outstanding features of this school are worth mentioning. Anatomical dissections were performed in Montpellier from the 12th and 13th centuries. In addition, surgery, a discipline usually scorned by mediaeval physicians and reserved for barber-surgeons and other bone setters, was taught there. These include, Guy de Chauliac, attached to the papal court in Avignon and whose treatise Chirurgia Magna was in annex to a Latin version of a book by AlbuCassis. This treatise would be a reference work for centuries.

History does not say whether these surgeons used opium and hashish as anaesthetics, as was sometimes done in the Middle Ages.

Petrus Hispanus taught at the Faculty of Medicine of Montpellier before he became pope under the name John XXI. And it was in Montpellier that François Rabelais, writer, defrocked monk and then reinstated and physician, received his degree of Doctor of Medicine.

Dr Francois Rabelais (1494-1553)

The history of osteoarthritis - Episode 4

Osteoarthritis in the Renaissance

Renaissance: Cultural Revolution and medical progress

Appearing first in Italy, the cultural and artistic movement of the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries known as the Renaissance was intended explicitly as a reaction to the "darkness" of the Middle Ages.

The first aim was to rediscover a supposed "golden age" of Antiquity beyond the mediaeval "scholastic" discipline which only allowed ideas in conformity with the dogmas of the Church to filter through from ancient knowledge.

But that did not stop this cultural revolution which, after Italy, extended to France and Flanders and influenced all the countries of Western Europe. While building on the past, men of the Renaissance were artists of a new genre (realism, control of perspective), builders and inventors.

The creative genius of Leonardo da Vinci, but also the ingenuity of the first commercial bankers testifies to this. There were also explorers with their insatiable curiosity who discovered the New World but also the human anatomy.

In the medical field the notions of "signs" and "symptoms" appeared and, for the first time, the word "rheumatism" received a modern definition. But let's not forget in all this effervescence, the first drugs derived from mineral nutrients and unquestionable progress in the field of surgery.

The medical conceptions of the Renaissance were sometimes called "pre-scientific" in the sense that the burden of proof was not necessary to state a theory, such as "physiological: observation and personal deductions were more than sufficient."

Certainly we would have to wait much longer for pharmaceutical chemistry to replace alchemy and for effective drugs to be invented; medical theories of the Renaissance, often inspired by the ancient concepts of "vital breath" or "humours", seem a little foggy to us. However, a new and sustainable concept remained, that of progress, which is probably the main legacy of that era for us.

Birth of modern anatomy

The first human anatomy amphitheatre was opened in Padua in 1490. In 1543, Flemish man Andreas Vesalius published De humani corporis fabrica (1514-1564), considered the most successful treatise on anatomy of that era. Andreas Vesalius (whose Frenchified name is André Vésale) taught anatomy at the University of Padua where he obtained his medical degree. His seven-volume book presents for the first time anatomical plates and descriptions based on the dissection of human cadavers.

Let's see how Vesalius describes the role of joint cartilage in a surprisingly modern way:

"Another role of cartilage which is not negligible, is to allow the bones to remain in continuity and move continuously and get less worn less by friction. The meeting points of bones built for movement would be easily damaged due to the dryness of the bones and by their contact if the surfaces they come into contact with and which form a joint were not completely and separately covered by cartilage which is sufficiently hard and soft to withstand the impacts of the bones and which, by yielding slightly, reduces the force of their contact. Cartilage not only serves to reduce the friction of the bones where they may become worn by contact but it seems so smooth and even that the end of a bone turns easily in its socket; no roughness hinders this facility of movement if a viscous and slippery fluid, comparable to the lubricant used to slide the ropes on pulleys, is present. "

The "viscous and slippery fluid" is none other than synovial fluid. Vesalius then describes the joint capsules, indicating that neither Galen, nor the Arab authors seem to have been aware of them.

But doctors were not the only ones interested in anatomy: artists, in the mood for realism, were not lagging far behind. Leonardo da Vinci, whose drawing is shown here, showing us how the human body can fit into a square or a circle, was reputed to have carried out thirty dissections. His principles of representation in perspective and in elevation were even supposedly taken up by Vesalius.

William of Baillou distinguished rheumatism and gout

It was William of Baillou (1538-1616), Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of Paris, who used the word "rheumatism" in the modern sense for the first time. In his book, Liber de rheumatismo et pleuritide dorsali, he designates acute rheumatoid arthritis under this term, but his description shows that it remains attached to the old Hippocratic theory of the humours:

"The humours (especially blood) flowing through the body provoke severe pain with their harmful substances. The condition we wrongly call catarrh should be called rheumatism. Rheumatism is a kind of disease of fluid receptacles in which the malignant humours flowing from inside to outside the body are deposited in the extremities and joints. What gout represents for a particular extremity, rheumatism represents for the entire body. "

Medical concepts were also evolving in other fields.

Girolamo Fracastoro (1483-1553) described the "French disease" (syphilis) and wrote other works in which he distinguished direct contagion and indirect contagion through the intermediary of objects.

In his Universa Medicina, Jean Fernel (1497-1558) places a strong emphasis on observation and distinguishes the observable signs of symptoms experienced by the patient. However, he remained a follower of the theory of "vital breath" dear to Galen.

Michael Servetus (1509-1553), much to his misfortune, discovered pulmonary circulation. To get the blood sent by the lungs to go back to the heart is contrary to Catholic dogma; Servetus did not have better luck with the Protestants when he left to seek refuge in Geneva where he was burnt at the stake with his books.

Dr Paracelsus' medicine

Paracelsus (1493-1541), whose real name was Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, was one of the first to criticise the concepts of the Ancients and in particular the theory of "vital breath". The impetuous Paracelsus was also struck off from the University of Basel for destroying the books of some of his medical colleagues.

Born in Switzerland, he became a doctor at the University of Vienna, and he toured Egypt, Arabia, the Promised Land and Byzantium to meet alchemists. Once back in Europe, he acquired a high reputation by applying alchemy, not to try to make gold, but to "use the virtue and power of the medications." His ideas on the necessary balance between the microcosm (human body) and macrocosm (nature) led him to believe that some diseases can be treated with chemicals or minerals. The abstruse theories of Paracelsus have no scientific basis, but his intellectual approach was innovative enough for him to be considered as one of the ancestors of modern drug therapy.

Arquebus and new surgical techniques

While arquebuses et bombards had begun to cause the first wounds by firearms, a man without academic qualifications and practising the much scorned manual profession of barber-surgeon was soon to reveal his exceptional talent. For physicians of that time, gun powder was poison and they thus had to cauterise the wound with... boiling oil.

It was in the headquarters in Turin in 1537 that Paré, not having enough oil to treat all the wounded, used a mixture of egg yolk and essence of rose only to find a much more positive outcome with this new treatment. From then on, he would consider one of the goals of surgery to be to minimise the suffering of those who were operated on. The idea was revolutionary at the time.

Building on his reputation, he was able to develop new techniques, including the use of ligatures in amputations, and new instruments and prostheses. His work, Ten Books of Surgery with the array of instruments necessary for it was quite successful, but Paré had to back-up his new techniques and theories with his opponents.

It was thanks to Ambroise Paré that surgery gained official recognition and would soon be taught at University.

When Venus had tuberculosis

An examination of ancient pictorial works, especially when they have the realism of the works of the Renaissance, gives us reason to suspect certain disorders of the people who appear in them and identify the emergence of relatively recent diseases. Rheumatism is one of the privileged topics of this research. Thus, the model who posed for the Birth of Venus by Botticelli (1490) presented signs of tuberculous arthritis and the philosopher Erasmus would have been suffering from rheumatoid arthritis.

It was under the guise of Vespucco Simonetta, who subsequently died of tuberculosis, that Boticelli represented Venus. Her fingers are slightly deflected and swollen and her ankles are also swollen. Some see in these subtle signs the likely presence of tuberculous arthritis.

The history of osteoarthritis - Episode 5

17th and 18th centuries: at the dawn of modern medicine

While the scholars of the Renaissance, despite their innovations, kept one foot in Antiquity those of these two centuries seem entirely focused on new ideas.

Descartes in France, but also Francis Bacon in England suggested a rationalism free from the religious dogma of the time as a means of advancing science.

Here we are at the beginning of a scientific approach that would lead to significant advances in the fields of physiology, the study of body tissues and the discovery of bacteria. Therapeutics follow in a rather timid way with the exception of the remarkable event of the first vaccination. One still had to wait to dispose of effective treatments against osteoarthritis, but medicine and surgery were getting organised, progress was set in motion and it was never to stop.

- Cartesian thought and the origins of the scientific revolution

- A new idea: medical studies attested by a diploma

- Was osteoarthritis less common than today?

- First description of Heberden's nodes

- From the reign of Henry IV to the First Empire, medicine was still powerless against osteoarthritis

- The Lame Devil was a believer in thermal cures

It was in his Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences that

René Descartes (1596-1650) laid the foundations of rationalism.

His "method" was based on four fundamental principles

- "The first of these was to accept nothing as true which I did not clearly recognise to be so: that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitation and prejudice in judgements and to accept in them nothing more than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly that I could have no occasion to doubt it.

- The second was to divide up each of the difficulties which I examined into as many parts as possible, and as seemed requisite in order that it might be resolved in the best manner possible.

- The third was to carry on my reflections in due order, commencing with objects that were the most simple and easy to understand, in order to rise little by little, or by degrees, to knowledge of the most complex, assuming an order, even if a fictitious one, among those which do not follow a natural sequence relatively to one another.

- The last was in all cases to make enumerations so complete and reviews so general that I should be certain of having omitted nothing."

By proposing a logical and almost mathematical sequence of ideas from indisputable evidence, Descartes broke definitively with scholastic thought and inaugurated the reign of scientific thought.

He contributed himself to the advancement of science by inventing analytic geometry and discovering the law of optical refraction. Defender of modern ideas, he was to become a firm believer in the theory of blood circulation proposed by the Englishman Harvey. His biological theories, however, show that his method could still be improved: he has the soul residing in the pineal gland by which it communicates with the body, which now seems strange. However, one can find a distant echo of the thought of Descartes in the concept currently in vogue, particularly in rheumatology, of "evidence-based medicine."

(1) Doctrine according to the dogmas of the Church, incorporating the philosophy of Aristotle in the twelfth century, taught in universities until the 17th century. Scholastic knowledge was based only on knowledge of the texts.

A new idea: medical studies attested by a diploma

In 1794, a decree of the National Convention ordered the establishment of three Schools of Health in Paris, Bordeaux and Montpellier. However, it was under the Consulate that the degree of Doctor of Medicine obtained in one of these schools became necessary for exercising medicine. The cardiologist Jean-Nicolas Corvisart was behind this reform.

The recognition of surgery

The Royal Academy of Surgery was founded in 1731. Physicians and Surgeons would subsequently study in the same Schools of Medicine where they would obtain the title of Doctor.

The creation of major hospitals

Henri IV had the Hospital of St. Louis constructed; Louis XIV decided that each major city should have its hospital. Originally intended for the accommodation of the poor, hospitals were quickly to become a place of medical education at the patients' bedside. Some hospital doctors specialised, such as Philippe Pinel (1745-1826), psychiatrist (then called alienist) known to have been the first to order that the mentally ill were no longer put in chains. Pinel exercised his talents at the Salpetriere hospice and prison for women which did not become a hospital until the early 19th century.

Was osteoarthritis less common than today?

The study of skeletons exhumed from the crypt of Christ Church, located in East London and used from 1729 to 1869 showed that men suffered more from osteoarthritis than women (2). The most common sites of osteoarthritis lesions were the shoulder, spine and hands. By contrast, osteoarthritis of large joints was uncommon, affecting 1.1% of men and 2.9% of women in the hips, 0.8% of men and 5.2% of women in the knees. The incidence of osteoarthritis is more common in the population currently living in the same area of London.

In all likelihood, these figures reflect both the difficulty of manual labour at the time (laundry washing could be responsible for affecting the knees in women) and, as in previous eras, a reduced life expectancy lowering apparent frequency of this disease which is, in part, due to ageing.

(2): Waldron HA. Prevalence and distribution of osteoarthritis in a population from Georgian and early Victorian London. Ann Rheum Dis 1991 ; 50 : 301-307.

The first description of Heberden's nodes.

The 17th and 18th centuries abound in descriptions of signs and symptoms of disease and it was in his Commentaries on the History and Cure of Diseases that William Heberden (1710-1801) described the digitorum nodi, signs of osteoarthritis now known as Heberden's nodes:

"What are these little hard nodules, with roughly the size of a pea, frequently observed on the fingers, especially just below the tip, near the joint? They have nothing to do with gout ... "

Heberden was thus the first to distinguish "his" famous nodes, affecting the distal interphalangeal joints, other rheumatic lesions of the fingers and gouty tophi.

From the reign of Henry IV to the First Empire, medicine was still powerless against osteoarthritis

Description of the circulation of blood by William Harvey in 1628, then the lymphatic circulation by Jean Pequet, first histological descriptions (study of body tissues) by the inventor of the microscope Anthony Van Leeuvenhoek and then by Marcello Malpighi and Xavier Bichat. The list of new knowledge acquired during these two centuries in the area of human physiology is truly impressive. Remember that Van Leeuvenhoek, once again, identified bacteria in 1683 after having discovered sperm in 1677.

These discoveries were sometimes difficult to impose when they were published. We know that Descartes was one of the protagonists of Harvey's theory of the circulatory system which was very rational and in which he no doubt recognised an application of his own "method". He had to differ on this point with two "anti-circulatory system" doctors, Riolan Jean and Guy Patin, for whom the arteries contained air and not blood. It can be assumed that the discussions were especially lively since it took the intervention of Louis XIV for the theory of the circulatory system to be imposed in France for good!

It was in the guise of Dr. Diafoirus, a professed anti-circulatory system doctor that Drs Riolan and Patin, but perhaps all of their colleagues as well, were ridiculed by Molière. If one believes the retorts of the Imaginary Invalid, the therapists of the time knew only three remedies: purges, bloodletting and enemas. As for the doctors described by Voltaire, they seriously wonder whether bleeding should be done on the healthy side or the diseased side.

These authors produced good caricatures of the medicine of the time. However, it is true that despite the striking evolution in physiological knowledge, advances in treatment were few and far between.

The reality is somewhat more nuanced, but it must be said that the lack of progress in treatment contrasts with the striking evolution in physiological knowledge.

Two notable exceptions are the use of digitalis (from which digitalin would be drawn later on) for certain heart conditions and, above all, the development in 1796 by Edward Jenner of the first vaccination successfully used against smallpox. One also notes the appearance of some new drugs (quinine for fever, ipecac used as an anti-diarrhoeal drug and tea and coffee used as psychostimulants).

All this did not do much for patients with osteoarthritis who, to ease their pain, only had recourse to the old (and ancient) concoction of willow bark, and for the wealthy, thermal cures. Unless they had recourse to homeopathy, the first "alternative" medicine (synonym of non-Cartesian?) proposed in 1796 by Christian Samuel Hahnemann. Visceral surgery had advanced (the first appendectomy was performed in 1763) but we are not yet in the era of the hip or knee prosthesis.

Edward Jenner

The Lame Devil was a believer in thermal cures

Prince Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (1754-1838), an exceptional diplomat and opportunistic enough to serve all regimes from the beginning of the Revolution to the Restoration, was affected by a consecutive club foot. Some dispute this version and now lean more towards a congenital club foot. The fact remains that the Lame Devil, who wore an orthopaedic shoe, took the waters at Bourbon l'Archambault for 30 consecutive years. No doubt he sought to relieve osteoarthritis of mechanical origin?